Paris AI Action Summit: A milestone for open and Public AI

As we close out the Paris AI Action Summit, one thing is clear: the conversation around open and Public AI is evolving—and gaining real momentum. Just over a year ago at Bletchley Park, open source AI was framed as a risk. In Paris, we saw a major shift. There is now a growing recognition that openness isn’t just compatible with AI safety and advancing public interest AI—it’s essential to it.

We have been vocal supporters of an ecosystem grounded in open competition and trustworthy AI —one where innovation isn’t walled off by dominant players or concentrated in a single geography. Mozilla, therefore, came to this Summit with a clear and urgent message: AI must be open, human-centered, and built for the public good. And across discussions, that message resonated.

Open source AI is entering the conversation in a big wayTwo particularly notable moments stood out:

- European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen spoke about Europe’s “distinctive approach to AI,” emphasizing collaborative, open-source solutions as a path forward.

- India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi reinforced this vision, calling for open source AI systems to enhance trust and transparency, reduce bias, and democratize technology.

These aren’t just words. The investments and initiatives announced at this Summit mark a real turning point. From the launch of Current AI, an initial $400M public interest AI partnership supporting open source development, to ROOST, a new nonprofit making AI safety tools open and accessible, to the €109 billion investment in AI computing infrastructure announced by President Macron, the momentum is clear. Add to that strong signals from the EU and India, and this Summit stands out as one of the most positive and proactive international gatherings on AI so far.

At the heart of this is Public AI—the idea that we need infrastructure beyond private, purely profit-driven AI. That means building AI that serves society and promotes true innovation even when it doesn’t fit neatly into short-term business incentives. The conversations in Paris show that we’re making progress, but there’s more work to do.

Looking ahead to the next AI summitMomentum is building, and we must forge onward. The next AI Summit in India will be a critical moment to review the progress on these announcements and ensure organizations like Mozilla—those fighting for open and Public AI infrastructure—have a seat at the table.

Mozilla is committed to turning this vision into reality—no longer a distant, abstract idea, but a movement already in motion.

A huge thanks to the organizers, partners, and global leaders driving this conversation forward. Let’s keep pushing for AI that serves humanity—not the other way around.

––Mitchell Baker

Chairwoman, Mozilla

Paris AI Action Summit Steering Committee Member

The post Paris AI Action Summit: A milestone for open and Public AI appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

ROOST: Open source AI safety for everyone

Today we want to point to one of the most exciting announcements at the Paris AI summit: the launch of ROOST, a new nonprofit to build AI safety tools for everyone.

ROOST stands for Robust Open Online Safety Tools, and it’s solving a clear and important problem: many startups, nonprofits, and governments are trying to use AI responsibly every day but they lack access to even the most basic safety tools and resources that are available to large tech companies. This not only puts users at risk but slows down innovation. ROOST has backing from top tech companies and philanthropies alike ensuring that a broad set of stakeholders have a vested stake in its success. This is critical to building accessible, scalable and resilient safety infrastructure all of us need for the AI era.

What does this mean practically? ROOST is building, open sourcing and maintaining modular building blocks for AI safety, and offering hands-on support by technical experts to enable organizations of all sizes to build and use AI responsibly. With that, organizations can tackle some of the biggest safety challenges such as eliminating child sexual abuse material (CSAM) from AI datasets and models.

At Mozilla, we’re proud to have helped kickstart this work, providing a small seed grant for the research at Columbia University that eventually turned into ROOST. Why did we invest early? Because we believe the world needs nonprofit public AI organizations that at once complement and serve as a counterpoint to what’s being built inside the big commercial AI labs. ROOST is exactly this kind of organization, with the potential to create the kind of public technology infrastructure the Mozilla, Linux, and Apache foundations developed in the previous era of the internet.

Our support of ROOST is part of a bigger investment in open source AI and safety.

In October 2023, before the AI Safety Summit in Bletchley Park, Mozilla worked with Professor Camille Francois and Columbia University to publish an open letter that stated “when it comes to AI Safety and Security, openness is an antidote not a poison.”

Over 1,800 leading experts and community members signed our letter, which compelled us to start the Columbia Convening series to advance the conversation around AI, openness, and safety. The second Columbia Convening (which was an official event on the road to the French AI Action Summit happening this week), brought together over 45 experts and builders in AI to advance practical approaches to AI safety. This work helped shape some of the priorities of ROOST and create a community ready to engage with it going forward. We are thrilled to see ROOST emerge from the 100+ leading AI open source organizations we’ve been bringing together the past year. It exemplifies the principles of openness, pluralism, and practicality that unite this growing community.

Much has changed in the last year. At the Bletchley Park summit, a number of governments and large AI labs had focused the debate on the so-called existential risks of AI — and were proposing limits on open source AI. Just 15 months later, the tide has shifted. With the world gathering at the AI Action Summit in France, countries are embracing openness as a key component of making AI safe in practical development and deployment contexts. This is an important turning point.

ROOST launches at exactly the right time and in the right place, using this global AI summit to gather a community that will create the practical building blocks we need to enable a safer AI ecosystem. This is the type of work that makes AI safety a field that everyone can shape and improve.

The post ROOST: Open source AI safety for everyone appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Mozilla Localization (L10N): L10n report: January 2025 Edition

Please note some of the information provided in this report may be subject to change as we are sometimes sharing information about projects that are still in early stages and are not final yet.

Welcome!Are you a locale leader and want us to include new members in our upcoming reports? Contact us!

New content and projects What’s new or coming up in Firefox desktop Tab GroupsTab groups are now available in Nightly 136! To create a group in Nightly, all you have to do is have two tabs open, click and drag one tab to the other, pause a sec and then drop. From there the tab group editor window will appear where you can name the group and give it a color. After saving, the group will appear on your tab bar.

Once you create a group, you can easily access your groups from the overflow menu on the right.

These work great in the sidebar and vertical tabs feature that was released in the Firefox Labs feature in Nightly 131!

New profile selectorThe new profile selector which we have been localizing over the previous months is now starting to roll out gradually to users in Nightly 136. SUMO has an excellent article about all the new changes which you can find here.

What’s new or coming up in web projects AMO and AMO FrontendThe team is planning to migrate/copy the Spanish (es) locale into four: es-AR, es-CL, es-ES, and es-MX. Per the community managers’ input, all locales will retain the suggestions that have not been approved at the time of migration. Be on the lookout for the changes in the upcoming week(s).

Mozilla AccountsThe Mozilla accounts team recently landed strings used in three emails planned to be sent over the course of 90 days, with the first happening in the coming weeks. These will be sent to inactive users who have not logged in or interacted with the Mozilla accounts service in 2 years, letting them know their account and data may be deleted.

What’s new or coming up in SUMOThe CX team is still working on 2025 planning. In the meantime, read a recap from our technical writer, Lucas Siebert about how 2024 went in this blog post. We will also have a community call coming up on Feb 5th at 5 PM UTC. Check out the agenda for more detail and we’d love to see you there!

Last but not least, we will be at FOSDEM 2025. Mozilla’s booth will be at the K building, level 1. Would love to see you if you’re around!

What’s new or coming up in Pontoon New Email FeaturesWe’re excited to announce two new email features that will keep you better informed and connected with your localization work on Pontoon:

Email Notifications: Opt in to receive notifications via email, ensuring you stay up to date with important events even when you’re away from the platform. You can choose between daily or weekly digests and subscribe to specific notification types only.

Monthly Activity Summary: If enabled, you’ll receive an email summary at the start of each month, highlighting your personal activity and key activities within your teams for the previous month.

Visit your settings to explore and activate these features today!

New Translation Memory tools are here!If you are a locale manager or translator, here’s what you can do from the new TM tab on your team page:

- Search, edit, and delete Translation Memory entries with ease.

- Upload .TMX files to instantly share your Translation Memories with your team.

These tools are here to save you time and boost the quality of suggestions from Machinery. Dive in and explore the new features today!

Moving to GitHub DiscussionsFeedback, support and conversations on new Pontoon developments have moved from Discourse to GitHub Discussions. See you there!

Newly published localizer facing documentation- How to test mozilla.org was updated to reflect some of the changes to the site in the last year or so.

Come check out our end of year presentation on Pontoon! A Youtube link and AirMozilla link are available.

Want to showcase an event coming up that your community is participating in? Contact us and we’ll include it.

Friends of the LionKnow someone in your l10n community who’s been doing a great job and should appear here? Contact us and we’ll make sure they get a shout-out!

Useful Links- #l10n-community channel on Element (chat.mozilla.org)

- Localization category on Discourse

- Mastodon

- L10n blog

If you want to get involved, or have any question about l10n, reach out to:

- Francesco Lodolo (flod) – Engineering Manager

- Bryan – l10n Project Manager

- Delphine – l10n Project Manager for mobile

- Peiying (CocoMo) – l10n Project Manager for mozilla.org, marketing, and legal

- Francis – l10n Project Manager for Common Voice, Mozilla Foundation

- Théo Chevalier – l10n Project Manager for Mozilla Foundation

- Matjaž (mathjazz) – Pontoon dev

- Eemeli – Pontoon, Fluent dev

Did you enjoy reading this report? Let us know how we can improve it.

Firefox Nightly: Firefox on macOS: now smaller and quicker to install!

Firefox is typically installed on macOS by downloading a DMG (Disk iMaGe) file, and dragging the Firefox.app into /Applications. These DMG files are compressed to reduce download time. As of Firefox 136, we’re making an under the hood change to them, and switching from bzip2 to lzma compression, which shrinks their size by ~9% and cuts decompression time by ~50%.

Why now?If you’re familiar with macOS packaging, you’ll know that LZMA support was introduced in macOS 10.15, all the way back in 2015. However, Firefox continued to support older versions of macOS until Firefox 116.0 was released in August 2023, which meant that we couldn’t use it prior to then.

But that still begs the question: why wait ~18 months later to realize these improvements? Answering that question requires a bit of explanation of how we package Firefox…

Packaging Firefox for macOS… on Linux!Most DMGs are created with hdiutil, a standard tool that ships with macOS. hdiutil is a fine tool, but unfortunately, it only runs natively on macOS. This a problem for us, because we package Firefox thousands of times per day, and it is impractical to maintain a fleet of macOS machines large enough to support this. Instead, we use libdmg-hfsplus, a 3rd party tool that runs on Linux, to create our DMGs. This allows us to scale these operations as much as needed for a fraction of the cost.

Why now, reduxUntil recently, our fork of libdmg-hfsplus only supported bzip2 compression, which of course made it impossible for us to use lzma. Thanks to some recent efforts by Dave Vasilevsky, a wonderful volunteer who previously added bzip2 support, it now supports lzma compression.

We quietly enabled this for Firefox Nightly in 135.0, and now that it’s had some bake time there, we’re confident that it’s ready to be shipped on Beta and Release.

Why LZMA?DMGs support many types of compression: bzip2, zlib, lzfse and lzma being the most notable. Each of these has strengths and weaknesses:

- bzip2 has the best compression (in terms of size) that is supported on all macOS versions, but the slowest decompression

- zlib has very fast decompression, at the cost of increased package size

- lzfse has the fastest decompression, but the second largest package size

- lzma has the second fastest decompression and the best compression in terms of size, at the cost of increased compression times

With all of this in mind, we chose lzma to make improvements on both download size and installation time.

You may wonder why download size is an important consideration, seeing as fast broadband connections are common these days. This may be true in many places, but not everyone has the benefits of a fast unmetered connection. Reducing download size has an outsized impact for users with slow connections, or those who pay for each gigabyte used.

What does this mean for you?Absolutely nothing! Other than a quicker installation experience, you should see absolutely no changes to the Firefox installation experience.

Of course, edge cases exist and bugs are possible. If you do notice something that you think may be related to this change please file a bug or post on discourse to bring it to our attention.

Get involved!If you’d like to be like Dave, and contribute to Firefox development, take a look at codetribute.mozilla.org. Whether you’re interested in automation and tools, the Firefox frontend, the Javascript engine, or many other things, there’s an opportunity waiting just for you!

Mozilla Addons Blog: Announcing the WebExtensions ML API

Greetings extension developers!

We wanted to highlight this just-published blog post from our AI team where they share some exciting news – we’re shipping a new experimental ML API in Firefox that will allow developers to leverage our AI Runtime to run offline machine learning tasks in their web extensions.

Head on over to Mozilla’s AI blog to learn more. After you’ve had a chance to check it out, we encourage you to share feedback, comments, or questions over on the Mozilla AI Discord (invite link).

Happy coding!

The post Announcing the WebExtensions ML API appeared first on Mozilla Add-ons Community Blog.

Running inference in web extensions

Image generated by DALL*E

We’re shipping a new API in Firefox Nightly that will let you use our Firefox AI runtime to run offline machine learning tasks in your web extension.

Firefox AI RuntimeWe’ve recently shipped a new component inside of Firefox that leverages Transformers.js (a JavaScript equivalent of Hugging Face’s Transformers Python library) and the underlying ONNX runtime engine. This component lets you run any machine learning model that is compatible with Transformers.js in the browser, with no server-side calls beyond the initial download of the models. This means Firefox can run everything on your device and avoid sending your data to third parties.

Web applications can already use Transformers.js in vanilla JavaScript, but running through our platform offers some key benefits:

- The inference runtime is executed in a dedicated, isolated process, for safety and robustness

- Model files are stored using IndexedDB and shared across origins

- Firefox-specific performance improvements are done to accelerate the runtime

This platform shipped in Firefox 133 to provide alt text for images in PDF.js, and will be used in several other places in Firefox 134 and beyond to improve the user experience.

We also want to unblock the community’s ability to experiment with these capabilities. Starting later today, developers will be able to access a new trial “ml” API in Firefox Nightly. This API is basically a thin wrapper around Firefox’s internal API, but with a few additional restrictions for user privacy and security.

There are two major differences between this API and most other WebExtensions APIs: the API is highly experimental and permission to use it must be requested after installation.

This new API is virtually guaranteed to change in the future. To help set developer expectations, the “ml” API is exposed under the “browser.trial” namespace rather than directly on the “browser” global object. Any API exposed on “browser.trial” may not be compatible across major versions of Firefox. Developers should guard against breaking changes using a combination of feature detection and strict_min_version declarations. You can see a more detailed description of how to write extensions with it in our documentation.

Running an inference taskPerforming inference directly in the browser is quite exciting. We expect people will be able to build compelling features using the browser’s data locally.

Like the original Transformers that inspired it, Transformers.js uses “tasks” to abstract away implementation details for performing specific kinds of ML workloads. You can find a description of all tasks that Transformers.js supports in the project’s official documentation.

For our first iteration, Firefox exposes the following tasks:

- text-classification – Assigning a label or class to a given text

- token-classification – Assigning a label to each token in a text

- question-answering – Retrieve the answer to a question from a given text

- fill-mask – Masking some of the words in a sentence and predicting which words should replace those masks

- summarization – Producing a shorter version of a document while preserving its important information.

- translation – Converting text from one language to another

- text2text-generation – converting one text sequence into another text sequence

- text-generation – Producing new text by predicting the next word in a sequence

- zero-shot-classification – Classifying text into classes that are unseen during training

- image-to-text – Output text from a given image

- image-classification – Assigning a label or class to an entire image

- image-segmentation – Divides an image into segments where each pixel is mapped to an object

- zero-shot-image-classification – Classifying images into classes that are unseen during training

- object-detection – Identify objects of certain defined classes within an image

- zero-shot-object-detection – Identify objects of classes that are unseen during training

- document-question-answering – Answering questions on document image

- image-to-image – Transforming a source image to match the characteristics of a target image or a target image domain

- depth-estimation – Predicting the depth of objects present in an image

- feature-extraction – Transforming raw data into numerical features that can be processed while preserving the information in the original dataset

- image-feature-extraction – Transforming raw data into numerical features that can be processed while preserving the information in the original image

For each task, we’ve selected a default model. See the list here EngineProcess.sys.mjs – mozsearch. These curated models are all stored in our Model Hub at https://model-hub.mozilla.org/. A Model Hub is how Hugging Face defines an online storage of models, see The Model Hub. Whether used by Firefox itself or an extension, models are automatically downloaded on the first use and cached.

Below is example below showing how to run a summarizer in your extension with the default model:

async function summarize(text) { await browser.trial.ml.createEngine({taskName: "summarization"}); const result = await browser.trial.ml.runEngine({args: [text]}); return result[0]["summary_text"]; }If you want to use another model, you can use any model published on Hugging Face by Xenova or the Mozilla organization. For now, we’ve restricted downloading models from those two organizations, but we might relax this limitation in the future.

To use an allow-listed model from Hugging Face, you can use an options object to set the “modelHub” option to “huggingface” and the “taskName” option to the appropriate task when creating an engine.

Let’s modify the previous example to use a model that can summarize larger texts:

async function summarize(text) { await browser.trial.ml.createEngine({ taskName: "summarization", modelHub: "huggingface", modelId: "Xenova/long-t5-tglobal-base-16384-book-summary" }); const result = await browser.trial.ml.runEngine({args: [text]}); return result[0]["summary_text"]; }Our PDF.js alt text feature follows the same pattern:

- Gets the image to describe

- Use the “image-to-text” task with the “mozilla/distilvit” model

- Run the inference and return the generated text

This feature is built directly into Firefox, but we’ve also made a web extension example out of it, that you can find in our source code and use as a basis to build your own. See https://searchfox.org/mozilla-central/source/toolkit/components/ml/docs/extensions-api-example. For instance, it includes some code to request the relevant permission, and a model download progress bar.

We’d love to hear from youThis API is our first attempt to enable the community to build on the top of our Firefox AI Runtime. We want to make this API as simple and powerful as possible.

We believe that offering this feature to web extensions developers will help us learn and understand if and how such an API could be developed as a web standard in the future.

We’d love to hear from you and see what you are building with this.

Come and say hi in our dedicated Mozilla AI discord #firefox-ai. Discord invitation: https://discord.gg/Jmmq9mGwy7

Last but not least, we’re doing a deep dive talk at the FOSDEM in the Mozilla room Sunday February 2nd in Brussels. There will be many interesting talks in that room, see: https://fosdem.org/2025/schedule/track/mozilla/

The post Running inference in web extensions appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Supercharge your day: Firefox features for peak productivity

Hi, I’m Tapan. As the leader of Firefox’s Search and AI efforts, my mission is to help users find what they are looking for on the web and stay focused on what truly matters. Outside of work, I indulge my geek side by building giant Star Wars Lego sets and sharing weekly leadership insights through my blog, Building Blocks. These hobbies keep me grounded and inspired as I tackle the ever-evolving challenges of the digital world.

I’ve always been fascinated by the internet — its infinite possibilities, endless rabbit holes and the wealth of knowledge just a click away. But staying focused online can feel impossible. I spend my days solving user problems, crafting strategies, and building products that empower people to navigate the web more effectively. Yet, even I am not immune to the pull of distraction. Let me paint you a picture of my daily online life. It’s a scene many of you might recognize: dozens of tabs open, notifications popping up from every corner, and a long to-do list staring at me. In this chaos, I’ve learned that staying focused requires intention and the right tools.

Over the years, I have discovered several Firefox features that are absolute game-changers for staying productive online:

1. Pinned Tabs: Anchor your essentialsPinned Tabs get me to my most essential tabs in one click. I have a few persistent pinned tabs — my email, calendar, and files — and a few “daily” pinned tabs — my “must-dos” of the day tabs. This is my secret weapon for keeping my workspace organized. Pinned Tabs stay put and don’t clutter my tab bar, making it easy to switch between key resources without hunting my tab list.

To pin a tab, right-click it and select “Pin Tab.” Now, your essential tabs will always be at your fingertips.

The “@” shortcut is my productivity superpower, taking me to search results in a flash. By typing “@amazon,” “@bing,” or “@history” followed by your search terms, you can instantly search those platforms or your browsing history without leaving your current page. This saves me time by letting me jump right to search results.

In the next Firefox update, we are making the search term persistent in the address bar so that you can use the address bar to refine your searches for supported sites.

To search supported sites, type “@” in the address bar and pick any engine from the supported list.

3. AI-powered summarization: Cut to the chaseThis is one of my favorite recent additions to Firefox. Our AI summarization feature can distill long articles or documents into concise summaries, helping you grasp the key points without wading through endless text. Recently, I used Firefox’s AI summarization to condense sections of research papers on AI. This helped me quickly grasp the key findings and apply them to our strategy discussions for enhancing Firefox’s AI features. Using AI to help build AI!

To use AI-powered summarization, type “about:preferences#experimental” in the address bar and enable “AI chatbot.” Pick your favorite chatbot and sign in. Select any text on a page you wish to summarize and right-click to pick “Ask <your chatbot>.” We are adding new capabilities to this list with every release.

4. Close Duplicate Tabs: Declutter your workspaceIf you are like me, you’ve probably opened the same webpage multiple times without realizing it. Firefox’s “Close Duplicate Tabs” feature eliminates this problem.

By clicking the tab list icon at the top-right corner of the Firefox window, you can detect and close duplicate tabs, keeping your workspace clean and reducing mental load. This small but mighty tool is for anyone prone to tab overload.

Reader View transforms cluttered web pages into clean, distraction-free layouts. You can focus entirely on the content by stripping away ads, pop-ups, and other distractions. Whether reading an article or researching, this feature keeps your mind on the task.

To enable it, click the Reader View icon in the address bar when viewing a page.

These Firefox features have transformed how I navigate the web, helping me stay focused, productive, and in control of my time online. Whether managing a complex task, diving into research, or just trying to stay on top of your daily tasks, these tools can help you take charge of your browsing experience.

What are your favorite Firefox productivity tips? I would love to hear how you customize Firefox to fit your life.

Let’s make the web work for us!

The post Supercharge your day: Firefox features for peak productivity appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Mozilla, EleutherAI publish research on open datasets for LLM training

Participants of the Dataset Convening in Amsterdam.

Update: Following the 2024 Mozilla AI Dataset Convening, AI builders and researchers publish best practices for creating open datasets for LLM training.

Participants of the Dataset Convening in Amsterdam.

Update: Following the 2024 Mozilla AI Dataset Convening, AI builders and researchers publish best practices for creating open datasets for LLM training.

Training datasets behind large language models (LLMs) often lack transparency, a research paper published by Mozilla and EleutherAI explores how openly licensed datasets that are responsibly curated and governed can make the AI ecosystem more equitable. The study is co-authored with thirty leading scholars and practitioners from prominent open source AI startups, nonprofit AI labs, and civil society organizations who attended the Dataset Convening on open AI datasets in June 2024.

Many AI companies rely on data crawled from the web, frequently without the explicit permission of copyright holders. While some jurisdictions like the EU and Japan permit this under specific conditions, the legal landscape in the United States remains murky. This lack of clarity has led to lawsuits and a trend toward secrecy in dataset practices—stifling transparency, accountability, and limiting innovation to those who can afford it.

For AI to truly benefit society, it must be built on foundations of transparency, fairness, and accountability—starting with the most foundational building block that powers it: data.

The research, “Towards Best Practices for Open Datasets for LLM Training,” outlines possible tiers of openness, normative principles, and technical best practices for sourcing, processing, governing, and releasing open datasets for LLM training, as well as opportunities for policy and technical investments to help the emerging community overcome its challenges.

Building toward a responsible AI future requires collaboration across legal, technical, and policy domains, along with investments in metadata standards, digitization, and fostering a culture of openness.

To help advance the field, the paper compiles best practices for LLM builders, including guidance on Encoding preferences in metadata, Data sourcing, Data Processing, Data Governance/Release, and Terms of Use.

To explore the recommendations check the full paper (also available on arXiv).

We are grateful to our collaborators – 273 Ventures, Ada Lovelace Institute, Alan Turing Institute, Cohere For AI, Common Voice, Creative Commons, Data Nutrition Project, Data Provenance Initiative, First Languages AI Reality (Mila), Gretel, HuggingFace, LLM360, Library Innovation Lab (Harvard), Open Future, Pleias, Spawning, The Distributed AI Research Institute, Together AI, and Ushahidi– for their leadership in this work, as well as Computer Says Maybe for their facilitation support.

We look forward to the conversations it will spark.

Previous post published on July 2, 2024:

Mozilla and EleutherAI brought together experts to discuss a critical question: How do we create openly licensed and open-access LLM training datasets and how do we tackle the challenges faced by their builders?On June 11, on the eve of MozFest House in Amsterdam, Mozilla and EleutherAI convened an exclusive group of 30 leading scholars and practitioners from prominent open-source AI startups, nonprofit AI labs and civil society organizations to discuss emerging practices for a new focus within the open LLM community: creating open-access and openly licensed LLM training datasets.

This work is timely. Although sharing training datasets was once common practice among many AI actors, increased competitive pressures and legal risks have made it almost unheard of nowadays for pre-training datasets to be shared or even described by their developers. However, just as open-source software has made the internet safer and more robust, we at Mozilla and EleutherAI believe open-access data is a public good that can empower developers worldwide to build upon each other’s work. It fosters competition, innovation and transparency, providing clarity around legal standing and an ability to stand up to scrutiny.

Leading AI companies want us to believe that training performant LLMs without copyrighted material is impossible. We refuse to believe this. An emerging ecosystem of open LLM developers have created LLM training datasets —such as Common Corpus, YouTube-Commons, Fine Web, Dolma, Aya, Red Pajama and many more—that could provide blueprints for more transparent and responsible AI progress. We were excited to invite many of them to join us in Amsterdam for a series of discussions about the challenges and opportunities of building an alternative to the current status quo that is open, legally compliant and just.

During the event, we drew on the learnings from assembling “Common Pile” (the soon-to-be-released dataset by EleutherAI composed only of openly licensed and public domain data) which incorporates many learnings from its hugely successful predecessor, “The Pile.” At the event, EleutherAI released a technical briefing and an invitation to public consultation on Common Pile.

Participants engaged in a discussion at “The Dataset Convening,” hosted by Mozilla and EleutherAI on June 11, 2024 to explore creating open-access and openly licensed LLM training datasets.

Participants engaged in a discussion at “The Dataset Convening,” hosted by Mozilla and EleutherAI on June 11, 2024 to explore creating open-access and openly licensed LLM training datasets.

Our goal with the convening was to bring in the experiences of open dataset builders to develop normative and technical recommendations and best practices around openly licensed and open-access datasets. Below are some highlights of our discussion:

- Openness alone does not guarantee legal compliance or ethical outcomes, we asked which decision points can contribute to datasets being more just and sustainable in terms of public good and data rights.

- We discussed what “good” looks like, what we want to avoid, what is realistic and what is already being implemented in the realm of sourcing, curating, governing and releasing open training datasets.

- Issues such as the cumbersome nature of sourcing public domain and openly licensed data (e.g. extracting text from PDFs), manual verification of metadata, legal status of data across jurisdictions, retractability of consent, preference signaling, reproducibility and data curation and filtering were recurring themes in almost every discussion.

- To enable more builders to develop open datasets and unblock the ecosystem, we need financial sustainability and smart infrastructural investments that can unblock the ecosystem.

- The challenges faced by open datasets today bear a resemblance to those encountered in the early days of open source software (data quality, standardization and sustainability). Back then, it was the common artifacts that united the community and provided some shared understanding and language. We saw the Dataset Convening as an opportunity to start exactly there and create shared reference points that, even if not perfect, will guide us in a common direction.

- The final insight round underscored that we have much to learn from each other: we are still in the early days of solving this immense challenge, and this nascent community needs to collaborate and think in radical and bold ways.

Participants at the Mozilla and EleutherAI event collaborating on best practices for creating open-access and openly licensed LLM training datasets.

Participants at the Mozilla and EleutherAI event collaborating on best practices for creating open-access and openly licensed LLM training datasets.

We are immensely grateful to the participants in the Dataset Convening (including some remote contributors):

- Stefan Baack — Researcher and Data Analyst, Insights, Mozilla

- Mitchell Baker — Chairwoman, Mozilla Foundation

- Ayah Bdeir — Senior Advisor, Mozilla

- Julie Belião — Senior Director of Product Innovation, Mozilla.ai

- Jillian Bommarito — Chief Risk Officer, 273 Ventures

- Kasia Chmielinski — Project Lead, Data Nutrition Project

- Jennifer Ding — Senior Researcher, Alan Turing Institute

- Alix Dunn — CEO, Computer Says Maybe

- Marzieh Fadaee — Senior Research Scientist, Cohere For AI

- Maximilian Gahntz — AI Policy Lead, Mozilla

- Paul Keller — Director of Policy and Co-Founder, Open Future

- Hynek Kydlíček — Machine Learning Engineer, HuggingFace

- Pierre-Carl Langlais — Co-Founder, Pleias

- Greg Leppert — Director of Product and Research, the Library Innovation Lab, Harvard

- EM Lewis-Jong — Director, Common Voice, Mozilla

- Shayne Longpre — Project Lead, Data Provenance Initiative

- Angela Lungati — Executive Director, Ushahidi

- Sebastian Majstorovic — Open Data Specialist, EleutherAI

- Cullen Miller — Vice President of Policy, Spawning

- Victor Miller — Senior Product Manager, LLM360

- Kasia Odrozek — Director, Insights, Mozilla

- Guilherme Penedo — Machine Learning Research Engineer, HuggingFace

- Neha Ravella — Research Project Manager, Insights Mozilla

- Michael Running Wolf — Co-Founder and Lead Architect, First Languages AI Reality, Mila

- Max Ryabinin — Distinguished Research Scientist, Together AI

- Kat Siminyu — Researcher, The Distributed AI Research Institute

- Aviya Skowron — Head of Policy and Ethics, EleutherAI

- Andrew Strait — Associate Director, Ada Lovelace Institute

- Mark Surman — President, Mozilla Foundation

- Anna Tumadóttir — CEO, Creative Commons

- Marteen Van Segbroeck — Head of Applied Science, Gretel

- Leandro von Werra — Chief Loss Officer, HuggingFace

- Maurice Weber — AI Researcher, Together AI

- Lee White — Senior Full Stack Developer, Ushahidi

- Thomas Wolf — Chief Science Officer and Co-Founder, HuggingFace

In the coming weeks, we will be working with the participants to develop common artifacts that will be released to the community, along with an accompanying paper. These resources will help researchers and practitioners navigate the definitional and executional complexities of advancing open-access and openly licensed datasets and strengthen the sense of community.

The event was part of the Mozilla Convening Series, where we bring together leading innovators in open source AI to tackle thorny issues and help move the community and movement forward. Our first convening was the Columbia Convening where we invited 40 leading scholars and practitioners to develop a framework for defining what openness means in AI. We are committed to continuing the efforts to support communities invested in openness around AI and look forward to helping grow and strengthen this movement.

The post Mozilla, EleutherAI publish research on open datasets for LLM training appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Streamline your schoolwork with Firefox’s PDF editor

As a student pursuing a master’s degree, I’ve spent too much time searching for PDF editors to fill out forms, take notes and complete projects. I discovered Firefox’s built-in PDF editor while interning at Mozilla as a corporate communications intern. No more giving out my email address or downloading dubious software, which often risks data. The built-in PDF tool on Firefox is a secure, efficient solution that saves me time. Here’s how it has made my academic life easier.

Fill out applications and forms effortlesslyRemember those days when you had to print a form, fill it out and then scan it back into your computer? I know, tedious. With Firefox’s PDF editor, you can fill in forms online directly from your browser. Just open the PDF in Firefox on your smartphone or computer, click the “text” button, and you’re all set to type away. It’s a gamechanger for all those scholarship applications and administrative forms, or even adult-life documents we consistently have to fill.

Highlight and annotate lecture slides for efficient note-taking

Highlight and annotate lecture slides for efficient note-taking

I used to print my professors’ lecture slides and study materials just to add notes. Now, I keep my annotations within the browser – highlighting key points and adding notes. You can even choose your text size and color. This capability not only enhances my note-taking, it saves some trees too. No more losing 50-page printed slides around campus.

Sign documents electronically without hassle

Sign documents electronically without hassle

Signing a PDF document was the single biggest dread I had as a millennial, a simple task made difficult. I used to have to search “free PDF editor” online, giving my personal information to make an account in order to use free software. Firefox makes it simple. Here’s how: Click the draw icon, select your preferred color and thickness, and draw directly on the document. Signing documents electronically finally feels like a 21st century achievement.

Easily insert and customize images in your PDFs

Easily insert and customize images in your PDFs

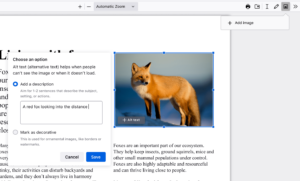

Sometimes, adding an image to your PDF is necessary, whether it’s a graph for a report or a picture for a project. Firefox lets you upload and adjust images right within the PDF. You can even add alternative text or alt-text to make your documents more accessible, ensuring everyone in your group can understand your work.

There are endless ways to make Firefox your own, however you choose to navigate the internet. We want to know how you customize Firefox. Let us know and tag us on X or Instagram at @Firefox.

The post Streamline your schoolwork with Firefox’s PDF editor appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Raising the bar: Why differential privacy is at the core of Anonym’s approach

Continuing our series on Anonym’s technology, this post focuses on Anonym’s use of differential privacy. Differential privacy is a cornerstone of Anonym’s approach to building confidential and effective data solutions. In this post, we’ll explain why we integrate differential privacy (DP) into all our systems and share how we tailor our implementation to meet the unique demands of advertising use cases.

As a reminder, Mozilla acquired Anonym over the summer of 2024, as a key pillar in its effort to raise the standards of privacy in the advertising industry. Separate from Mozilla surfaces like Firefox, which work to protect users from excessive data collection, Anonym provides ad tech infrastructure that focuses on improving privacy and limiting data shared between advertisers and ad platforms.

What is differential privacy?Created in 2006 by Cynthia Dwork and her collaborators, DP provides a principled method to generate insights without compromising individual confidentiality. This is typically achieved by adding carefully calibrated statistical noise to computations, making individual data points indistinguishable.

Differential Privacy has been used in a number of different contexts to enhance user privacy, notably in the US Census and for public health use cases. This post will focus on why Anonym believes DP is an essential tool in how we create performance with our partners, while preserving privacy. For those interested in learning more about the theoretical underpinnings of DP, we’ve linked some of our favorite resources at the end of this post.

Why differential privacy for advertising use cases?Simply put, we believe that differential privacy offers improved privacy to users while allowing analysis on ad performance. Many traditional privacy techniques used in advertising are at high risk of exposing user data, even if inadvertently. One of the most common traditional techniques is only returning aggregates when more than a minimum number of users have contributed (thresholding). The two examples below illustrate where thresholding can still result in revealing user data.

Example 1: In attribution reporting, measuring partially overlapping groups can reveal individual user information. Imagine a dataset that provides attribution data segmented by age group and we have implemented a threshold of ten – meaning we will only provide reporting if we have at least ten conversions for the segment. Suppose there are only nine purchasers in the “18-20” age group. Thresholding might suppress this entire segment to protect privacy. However, if a larger group—such as users exposed to ads targeted at users aged 18 to 35—is reported, and this larger group contains just one more user, it becomes relatively straightforward to deduce that the additional user is a purchaser. This demonstrates how thresholding alone can unintentionally expose individual data by leaving related groups visible.

Example 2: Imagine a clean room consistently suppresses results for aggregations with fewer than ten individuals but always reports statistics for groups with ten or more, an attacker could introduce minor changes to the input data—such as adding a single individual—to observe how the output changes. By monitoring these changes, the attacker could reverse-engineer the behavior of the individual added.

The FTC has recently shared its perspective that relying purely on confidential computing by using data clean rooms may not adequately protect people’s privacy and we agree – users need more protection than afforded by simple aggregation and thresholding.

The advantages of differential privacyDifferential privacy offers several key improvements over the methods discussed above:

- Mathematical guarantees: Differential privacy provides quantifiable and provable mathematical guarantees about the confidentiality of individuals in a dataset, ensuring that the risk of revealing individual-level information is reduced. Additionally DP has a concept called composibility which states that even if we look at a large number of results over time, we can still quantify the privacy.

- Protection from auxiliary information: DP ensures that even if a party such as an ad platform possesses additional information about users (which is typically the case), they cannot confidently identify specific individuals from the dataset.

- Minimal impact on utility: When implemented well, the actionability of DP-protected outputs is comparable to results without DP, and there is no need to suppress results. This means advertisers can trust their data to inform decision-making without compromising individual user confidentiality.

With these benefits, DP offers better privacy guarantees than other methods. We don’t need to think through all the potential edge cases like we saw for thresholding. For advertisers and platforms, the choice is clear: why wouldn’t you want the strongest available privacy protection?

How Anonym implements differential privacyAt Anonym, we recognize that one-size-fits-all solutions rarely work, especially in the complex world of advertising. That’s why all our DP implementations are bespoke to the ad platform and designed to maximize utility for each of their advertiser use cases.

Tailoring DP to the problemOur approach takes into account the unique requirements of each advertising campaign. We use differential privacy for our ML-based solutions, but let’s use a measurement example:

- Measurement goals: Are we measuring the number of purchases, the amount purchased, or both? We only want to release the necessary information to maximize utility.

- Decision context: What metrics matter most to the advertiser? In lift that could be understanding incrementality vs. statistical significance. We can tailor what we return to meet the advertiser’s needs. This increases utility by avoiding releasing information that will not change decision making.

- Dimensional Complexity: What dimensions are we trying to measure? Is there a hierarchy? We can improve utility by taking advantage of underlying data structures.

To create solutions that are both private and actionable, our development process involves close collaboration between our teams of differential privacy experts and advertising experts.

Differential privacy experts play a crucial role in ensuring the mathematical correctness of implementations. This is a critical step because DP guarantees are only valid if implemented correctly. These DP experts carefully match the DP method to the specific problem, selecting the option that offers the highest utility. Additionally, these experts incorporate the latest innovations in DP to further enhance the effectiveness and practicality of the solutions.

Advertising experts, on the other hand, help ensure the base ads algorithms are optimized to deliver high-utility results. Their insights further optimize DP methods for decision-making, aligning the outputs with the specific needs of advertisers.

This multidisciplinary approach helps our solutions meet rigorous mathematical privacy standards while empowering advertisers to make effective, data-driven decisions.

ConclusionIn an era of increasing data collection and heightened privacy concerns, differential privacy is a key technique for protecting the confidentiality of individual data without sacrificing utility. At Anonym, we’ve built DP into the foundation of our systems because we believe it’s the best way to deliver actionable insights while safeguarding user trust.

By combining deep expertise in DP with a nuanced understanding of advertising, we’re able to offer solutions that meet the needs of advertisers, regulators, and, most importantly, people.

Further Reading: Check out our favorite resources to learn more about differential privacy:

- Programming Differential Privacy

- This blog series

- Open DP’s resources (here)

The post Raising the bar: Why differential privacy is at the core of Anonym’s approach appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

A different take on AI safety: A research agenda from the Columbia Convening on AI openness and safety

On Nov. 19, 2024, Mozilla and Columbia University’s Institute of Global Politics held the Columbia Convening on AI Openness and Safety in San Francisco. The Convening, which is an official event on the road to the AI Action Summit to be held in France in February 2025, took place on the eve of the Convening of the International Network of AI Safety Institutes. In the convening we brought together over 45 experts and practitioners in AI to advance practical approaches to AI safety that embody the values of openness, transparency, community-centeredness and pragmatism.

Prior to the event on Nov. 19, twelve of these experts formed our working group and collaborated over six weeks on a thorough, 40-page “backgrounder” document that helped frame and focus our-person discussions, and design tracks for participants to engage with throughout the convening.

The Convening explored the intersection of Open Source AI and Safety, recognizing two key dynamics. First, while the open source AI ecosystem continues to gain unprecedented momentum among practitioners, it seeks more open and interoperable tools to ensure responsible and trustworthy AI deployments. Second, this community is approaching safety systems and tools differently, favoring open source values that are decentralized, pluralistic, culturally and linguistically diverse, and emphasizing transparency and auditability. Our discussions resulted in a concrete, collective and collaborative output: “A Research Agenda for a Different AI Safety,” which is organized around five working tracks.

We’re grateful to the French Government’s AI Action Summit for co-sponsoring our event as a critical milestone on the “Road to the AI Action Summit” in February, and to the French Minister for Artificial Intelligence who joined us to give closing remarks at the end of the day.

In the coming months, we will publish the proceedings of the conference. In the meantime, a summarized readout of the discussions from the convening are provided below.

Readout from Convening:

What’s missing from taxonomies of harm and safety definitions?

Readout from Convening:

What’s missing from taxonomies of harm and safety definitions?

Participants grappled with the premise that there is no such thing as a universally ‘aligned’ or ‘safe’ model. We explored the ways that collective input can both support better-functioning AI systems across use cases, help prevent harmful uses of AI systems, and further develop levers of accountability. Most AI safety challenges involve complex sociotechnical systems where critical information is distributed across stakeholders and key actors often have conflicts of interest, but participants noted that open and participatory approaches can help build trust and advance human agency amidst these interconnected and often exclusionary systems.

Participants examined limitations in existing taxonomies of harms and explored what notions of safety put forth by governments and big tech companies can fail to capture. AI-related harms are often narrowly defined by companies and developers for practical reasons, who often overlook or de-emphasize broader systemic and societal impacts on the path to product launches. The Convening’s discussions emphasized that safety cannot be adequately addressed without considering domain-specific contexts, use cases, assumptions, and stakeholders. From automated inequality in public benefits systems to algorithmic warfare, discussions highlighted how safety discussions accompanying AI systems’ deployments can become too abstract and fail to center diverse voices and the individuals and communities who are actually harmed by AI systems. A key takeaway was to continue to ensure AI safety frameworks center human and environmental welfare, rather than predominantly corporate risk reduction. Participants also emphasized that we cannot credibly talk about AI safety without acknowledging the use of AI in warfare and critical systems, especially as there are present day harms playing out in various parts of the world.

Drawing inspiration from other safety-critical fields like bioengineering, healthcare, and public health, and lessons learned from adjacent discipline of Trust and Safety, the workshop proposed targeted approaches to expand AI safety research. Recommendations included developing use-case-specific frameworks to identify relevant hazards, defining stricter accountability standards, and creating clearer mechanisms for harm redressal.

Safety tooling in open AI stacksAs the ecosystem of open source tools for AI safety continues to grow, developers need better ways to navigate it. Participants mapped current technical interventions and related tooling, and helped identify gaps to be filled for safer systems deployments. We discussed the need for reliable safety tools, especially as post-training models and reinforcement learning continues to evolve. Conversants noted that high deployment costs, lack of safety tooling and methods expertise, and fragmented benchmarks can also hinder safety progress in the open AI space. Resources envisioned included dynamic, standardized evaluations, ensemble evaluations, and readily available open data sets that could help ensure that safety tools and infrastructure remain relevant, useful, and accessible for developers. A shared aspiration emerged: to expand access to AI evaluations while also building trust through transparency and open-source practices.

Regulatory and incentive structures also featured prominently, as participants emphasized the need for clearer guidelines, policies, and cross-sector alignment on safety standards. The conversation noted that startups and larger corporations often approach AI safety differently due to contrasting risk exposures and resourcing realities, yet both groups need effective monitoring tools and ecosystem support. The participants explored how insufficient taxonomical standards, lack of tooling for data collection, and haphazard assessment frameworks for AI systems can hinder progress and proposed collaborative efforts between governments, companies, and non-profits to foster a robust AI safety culture. Collectively, participants envisioned a future where AI safety systems compete on quality as much as AI models themselves.

The future of content safety classifiersAI systems developers often have a hard time finding the right content safety classifier for their specific use case and modality, especially when developers need to also fulfill other requirements around desired model behaviors, latency, performance needs, and other considerations. Developers need a better approach for standardizing reporting about classifier efficacy, and for facilitating comparisons to best suit their needs. The current lack of an open and standardized evaluation mechanism across various types of content or languages can also lead to unknown performance issues, requiring developers to perform a series of time-consuming evaluations themselves — adding additional friction to incorporating safety practices into their AI use cases.

Participants chartered a future roadmap for open safety systems based on open source content safety classifiers, defining key questions, estimating necessary resources, and articulating research agenda requirements while drawing insights from past and current classifier system deployments. We explored gaps in the content safety filtering ecosystem, considering both developer needs and future technological developments. Participants paid special attention to the challenges posed in combating child sexual abuse material and identifying other harmful content. We also noted the limiting factors and frequently Western-centric nature of current tools and datasets for this purpose, emphasizing the need for multilingual, flexible, and open-source solutions. Discussions also called for resources that are accessible to developers across diverse skill levels, such as a “cookbook” offering practical steps for implementing and evaluating classifiers based on specific safety priorities, including child safety and compliance with international regulations.

The workshop underscored the importance of inclusive data practices, urging a shift from rigid frameworks to adaptable systems that cater to various cultural and contextual needs and realities. Proposals included a central hub for open-source resources, best practices, and evaluation metrics, alongside tools for policymakers to develop feasible guidelines. Participants showed how AI innovation and safety could be advanced together, prioritizing a global approach to AI development that works in underrepresented languages and regions.

Agentic riskWith growing interest in “agentic applications,” participants discussed how to craft meaningful working definitions and mappings of the specific needs of AI-system developers in developing safe agentic systems. When considering agentic AI systems, many of the usual risk mitigation approaches for generative AI systems — such as content filtering or model tuning — run into limitations. In particular, such approaches are often focused on non-agentic systems that only generate text or images, whereas agentic AI systems take real-world actions that carry potentially significant downstream consequences. For example, an agent might autonomously book travel, file pull requests on complex code bases, or even take arbitrary actions on the web, introducing new layers of safety complexity. Agent safety can present a fundamentally different challenge as agents perform actions that may appear benign on their own while potentially leading to unintended or harmful consequences when combined.

Discussions began with a foundational question: how much trust should humans place in agents capable of decision-making and action? Through case studies that included AI agents being used to select a babysitter and book a vacation, participants analyzed risks including privacy leaks, financial mismanagement, and misalignment of objectives. A clear distinction emerged between safety and reliability; while reliability errors in traditional AI might be inconveniences, errors in autonomous agents could cause more direct, tangible, and irreversible harm. Conversations highlighted the complexity of mitigating risks such as data misuse, systemic bias, and unanticipated agent interactions, underscoring the need for robust safeguards and frameworks.

Participants proposed actionable solutions focusing on building transparent systems, defining liability, and ensuring human oversight. Guardrails for both general-purpose and specialized agents, including context-sensitive human intervention thresholds and enhanced user preference elicitation, were also discussed. The group emphasized the importance of centralized safety standards and a taxonomy of agent actions to prevent misuse and ensure ethical behavior. With the increasing presence of AI agents in sectors like customer service, cybersecurity, and administration, Convening members stressed the urgency of this work.

Participatory inputsParticipants examined how participatory inputs and democratic engagement can support safety tools and systems throughout development and deployment pipelines, making them more pluralistic and better adapted to specific communities and contexts. Key concepts included creating sustainable structures for data contribution, incentivizing safety in AI development, and integrating underrepresented voices, such as communities in the Global Majority. Participants highlighted the importance of dynamic models and annotation systems that balance intrinsic motivation with tangible rewards. The discussions also emphasized the need for common standards in data provenance, informed consent, and participatory research, while addressing global and local harms throughout AI systems’ lifecycles.

Actionable interventions such as fostering community-driven AI initiatives, improving tools for consent management, and creating adaptive evaluations to measure AI robustness were identified. The conversation called for focusing on democratizing data governance by involving public stakeholders and neglected communities, ensuring data transparency, and avoiding “golden paths” that favor select entities. The workshop also underscored the importance of regulatory frameworks, standardized metrics, and collaborative efforts for AI safety.

Additional discussionSome participants discussed the tradeoffs and false narratives embedded in the conversations around open source AI and national security. A particular emphasis was placed on the present harms and risks from AI’s use in military applications, where participants stressed that these AI applications cannot solely be viewed as policy or national security issues, but must also be viewed as technical issues too given key challenges and uncertainties around safety thresholds and system performance.

ConclusionOverall, the Convening advanced discussions in a manner that showed that a pluralistic, collaborative approach to AI safety is not only possible, but also necessary. It showed that leading AI experts and practitioners can bring much needed perspectives to a debate dominated by large corporate and government actors, and demonstrated the importance of a broader range of expertise and incentives. This framing will help ground a more extensive report on AI safety that will follow from this Convening in the coming months.

We are immensely grateful to the participants in the Columbia Convening on AI Safety and Openness; as well as our incredible facilitator Alix Dunn from Computer Says Maybe, who continues to support our community in finding alignment around important socio-technical topics at the intersection of AI and Openness.

The list of participants at the Columbia Convening is below, individuals with an asterisk were members of the working group

- Guillaume Avrin – National Coordinator for Artificial Intelligence, Direction Générale des Entreprises

- Adrien Basdevant – Tech Lawyer, Entropy

- Ayah Bdeir* – Senior Advisor, Mozilla

- Brian Behlendorf – Chief AI Strategist, The Linux Foundation

- Stella Biderman– Executive Director, EleutherAI

- Abeba Birhane – Adjunct assistant professor, Trinity College Dublin

- Rishi Bommasani – Society Lead, Stanford CRFM

- Herbie Bradley – PhD Student, University of Cambridge

- Joel Burke – Senior Policy Analyst, Mozilla

- Eli Chen – CTO & Co-Founder, Credo AI

- Julia DeCook, PhD – Senior Policy Specialist, Mozilla

- Leon Derczynski – Principal research scientist, NVIDIA Corp & Associate professor, IT University of Copenhagen

- Chris DiBona – Advisor, Unaffiliated

- Jennifer Ding – Senior researcher, The Alan Turing Institute

- Bonaventure F. P. Dossou – PhD Student, McGill University/Mila Quebec AI Institute

- Alix Dunn – Facilitator, Computer Says Maybe

- Nouha Dziri* – Head of AI Safety, Allen Institute for AI

- Camille François* – Associate Professor, Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs

- Krishna Gade – Founder & CEO, Fiddler AI

- Will Hawkins* – PM Lead for Responsible AI, Google DeepMind

- Ariel Herbert-Voss – Founder and CEO, RunSybil

- Sara Hooker – VP Research, Head of C4AI, Cohere

- Yacine Jernite* – Head of ML and Society, HuggingFace

- Sayash Kapoor* – Ph.D. candidate, Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy

- Heidy Khlaaf* – Chief AI Scientist, AI Now Institute

- Kevin Klyman – AI Policy Researcher, Stanford HAI

- David Krueger – Assistant Professor, University of Montreal / Mila

- Greg Lindahl – CTO, Common Crawl Foundation

- Yifan Mai – Research Engineer, Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM)

- Nik Marda* – Technical Lead, AI Governance, Mozilla

- Petter Mattson – President, ML Commons

- Huu Nguyen – Co-founder, Partnership Advocate, Ontocord.ai

- Mahesh Pasupuleti – Engineering Manager, Gen AI, Meta

- Marie Pellat* – Lead Applied Science & Safety, Mistral

- Ludovic Péran* – AI Product Manager

- Deb Raji* – Mozilla Fellow

- Robert Reich – Senior Advisor, U.S. Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute

- Sarah Schwetmann – Co-Founder, Transluce & Research Scientist, MIT

- Mohamed El Amine Seddik – Lead Researcher, Technology Innovation Institute

- Juliet Shen – Product Lead, Columbia University SIPA

- Divya Siddarth* – Co-Founder & Executive DIrector, Collective Intelligence Project

- Aviya Skowron* – Head of Policy and Ethics, EleutherAI

- Dawn Song – Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at UC Berkeley

- Joseph Spisak* – Product Director, Generative AI @Meta

- Madhu Srikumar* – Head of AI Safety Governance, Partnership on AI

- Victor Storchan – ML Engineer

- Mark Surman – President, Mozilla

- Audrey Tang* – Cyber Ambassador-at-Large, Taiwan

- Jen Weedon – Lecturer and Researcher, Columbia University

- Dave Willner – Fellow, Stanford University

- Amy Winecoff – Senior Technologist, Center for Democracy & Technology

The post A different take on AI safety: A research agenda from the Columbia Convening on AI openness and safety appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

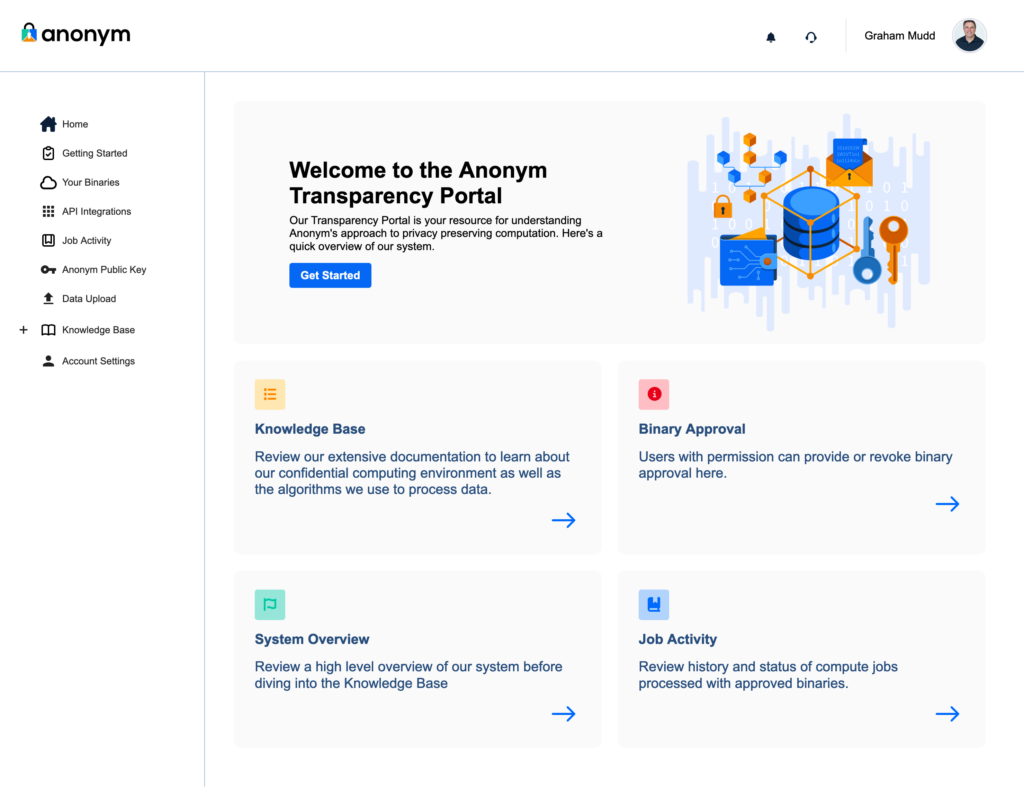

Building trust through transparency: A deep dive into the Anonym Transparency Portal

Continuing our series on Anonym’s technology, this post focuses on the Transparency Portal, a critical tool designed to give our partners comprehensive visibility into the processes and algorithms that handle their data. As a reminder, Mozilla acquired Anonym over the summer of 2024, as a key pillar in its effort to raise the standards of privacy in the advertising industry. These privacy concerns are well documented, as described in the US Federal Trade Commission’s recent report. Separate from Mozilla surfaces like Firefox, which work to protect users from invasive data collection, Anonym is ad tech infrastructure that focuses on improving privacy measures for data commonly shared between advertisers and ad networks.

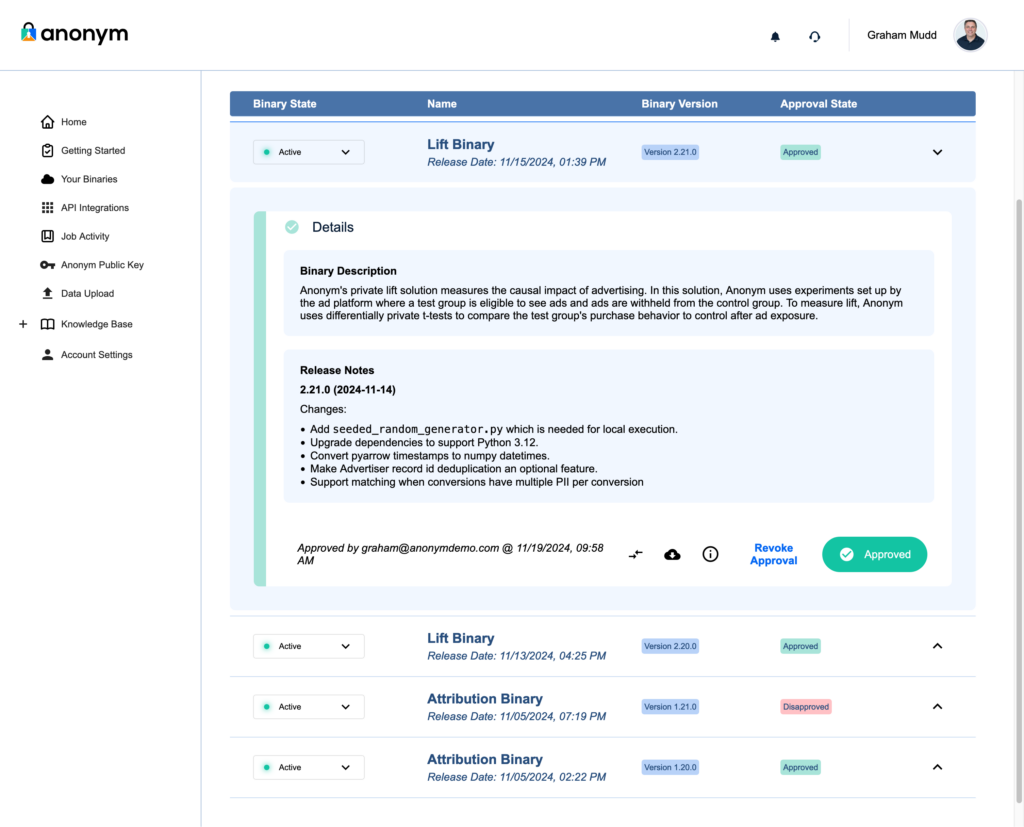

Anonym uses Trusted Execution Environments, which include the benefit of providing security to users through the attestation processes. As discussed in our last post, this guarantees that only approved code can be run. Anonym wanted our customers to be able to participate in this process without the burden of overly complicated technical integration. For this reason Anonym developed the Transparency Portal and a process we call binary review. Anonym’s Transparency Portal provides comprehensive review capabilities and operational control over data processing to partners.

The Transparency Portal: Core features

The Transparency Portal: Core features

The Transparency Portal is designed to offer clear, actionable insights into how data is processed while enabling partners to maintain strict control over the use of their data. The platform’s key components include:

- Knowledge Base

Anonym provides comprehensive documentation of all aspects of our system, including: 1) the architecture and security practices for the trusted execution environment Anonym uses for data processing; 2) details on the methodology used for the application, such as our measurement solutions (Private Lift, Private Attribution) and 3) how Anonym uses differential privacy to help preserve the anonymity of individuals. - Binary Review and Approval

Partners can review and approve each solution Anonym offers, a process we call Binary Review. On the Your Binaries tab, partners can download source code, inspect cryptographic metadata, and approve or revoke binaries (i.e. the code behind the solutions) as needed. This ensures that only vetted and authorized code can process partner data.

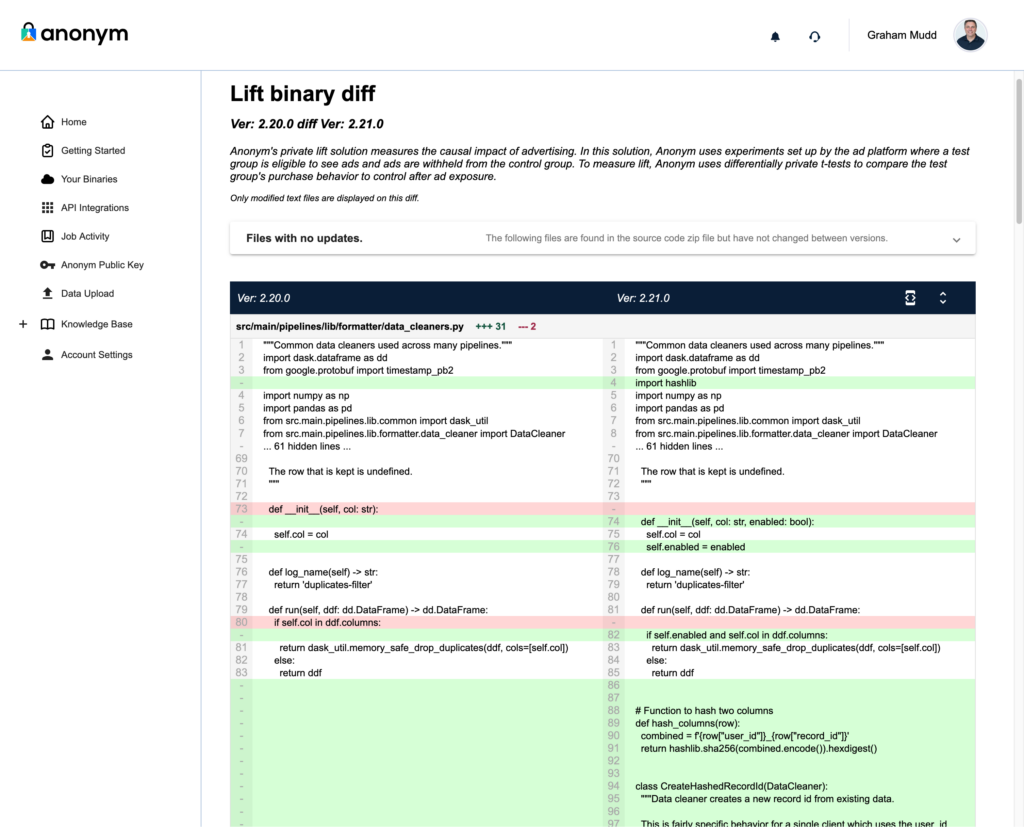

- Code Comparison Tool

For partners managing updates or changes to binaries, the portal includes a source code comparison tool. This tool provides line-by-line visibility into changes (aka ‘diffs’) between binary versions, highlighting additions, deletions, and modifications. Combined with detailed release notes, this feature enables partners to quickly assess updates and make informed decisions.

- Job History Logs

A complete log of all data processing jobs enables tracing of all data operations. Each entry details the algorithm used, the data processed, and the associated binary version, creating an immutable audit trail for operational oversight and to help support regulatory compliance. - Access and Role Management

The portal allows partners to manage their internal access rights. Administrative tools enable the designation of users who can review documentation, approve binaries, and monitor processing activities.

We believe visibility and accountability are foundational requirements of any technology, and especially for systems that process consumer data, such as digital advertising. By integrating comprehensive review, approval, and audit capabilities, the Transparency Portal ensures that our partners have full visibility into how their data is used for advertising purposes while maintaining strict data security and helping to support compliance efforts.

In our next post, we’ll delve into the role of encryption and secure data transfer in Anonym’s platform, explaining how these mechanisms work alongside the Transparency Portal and the TEE to protect sensitive data at every stage of processing.

The post Building trust through transparency: A deep dive into the Anonym Transparency Portal appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

Proposed contractual remedies in United States v. Google threaten vital role of independent browsers

Giving people the ability to shape the internet and their experiences on it is at the heart of Mozilla’s manifesto. This includes empowering people to choose how they search.

On Nov. 20, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) filed proposed remedies in the antitrust case against Google. The judgment outlines the behavioral and structural remedies proposed by the government in order to restore search engine competition.

Mozilla is a long-time champion of competition and an advocate for reforms that create a level playing field in digital markets. We recognize the DOJ’s efforts to improve search competition for U.S. consumers. It is important to understand, however, that the outcomes of this case will have impacts that go far beyond any one company or market.

As written, the proposed remedies will force smaller and independent browsers like Firefox to fundamentally reexamine their entire operating model. By jeopardizing the revenue streams of critical browser competitors, these remedies risk unintentionally strengthening the positions of a handful of powerful players, and doing so without delivering meaningful improvements to search competition. And this isn’t just about impacting the future of one browser company — it’s about the future of the open and interoperable web.

Firefox and searchSince the launch of Firefox 1.0 in 2004, we have shipped with a default search engine, thinking deeply about search and how to provide meaningful choice for people. This has always meant refusing any exclusivity; instead we preinstall multiple search options and we make it easy for people to change their search engine — whether setting a general default or customizing it for individual searches.

We have always worked to provide easily accessible search alternatives alongside territory-specific options — an approach we continue today. For example, in 2005, our U.S. search options included Yahoo, eBay, Creative Commons and Amazon, alongside Google.

Today, Firefox users in the U.S. can choose between Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, Amazon, eBay and Wikipedia directly in the address bar. They can easily add other search engines and they can also benefit from Mozilla innovations, like Firefox Suggest.

For the past seven years, Google search has been the default in Firefox in the U.S. because it provides the best search experience for our users. We can say this because we have tried other search defaults and supported competitors in search: in 2014, we switched from Google to Yahoo in the U.S. as they sought to reinvigorate their search product. There were certainly business risks, but we felt the risk was worth it to further our mission of promoting a better internet ecosystem. However, that decision proved to be unsuccessful.

Firefox users — who demonstrated a strong preference for having Google as the default search engine — did not find Yahoo’s product up to their expectations. When we renewed our search partnership in 2017, we did so with Google. We again made certain that the agreement was non-exclusive and allowed us to promote a range of search choices to people.

The connection between browsers and search that existed in 2004 is just as important today. Independent browsers like Firefox remain a place where search engines can compete and users can choose freely between them. And the search revenue Firefox generates is used to advance our manifesto, through the work of the Mozilla Foundation and via our products — including Gecko, Mozilla’s browser engine.

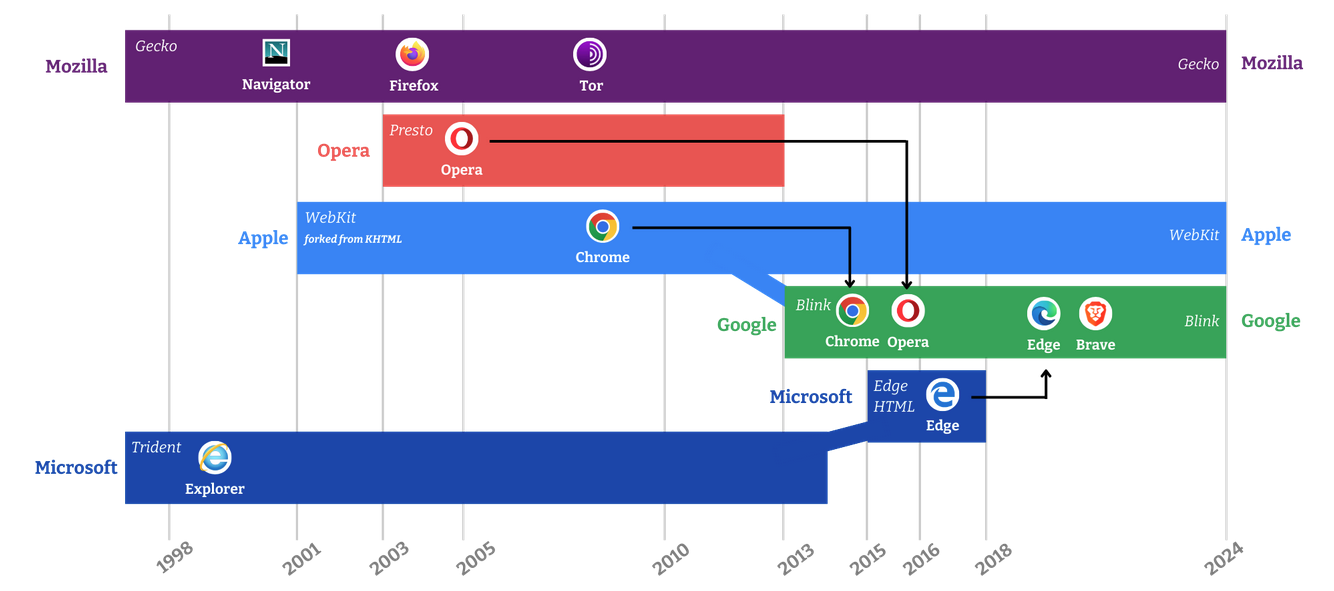

Browsers, browser engines and the open webSince launching Firefox in 2004, Mozilla has pioneered groundbreaking technologies, championing open-source principles and setting critical standards in online security and privacy. We also created or contributed to many developments for the wider ecosystem, some (like Rust and Let’s Encrypt) have continued to flourish outside of Mozilla. Much of this is made possible by developing and maintaining the Gecko browser engine.

Browser engines (not to be confused with search engines) are little-known but they are the technology powering your web browser. They determine much of the speed and functionality of browsers, including many of the privacy and security properties.

In 2013, there were five major browser engines. In 2024, due to the great expense and expertise needed to run a browser engine, there are only three left: Apple’s WebKit, Google’s Blink and Mozilla’s Gecko — which powers Firefox.

Apple’s WebKit primarily runs on Apple devices, leaving Google and Mozilla as the main cross-platform browser engine developers. Even Microsoft, a company with a three trillion dollar market cap, abandoned its Trident browser engine in 2019. Today, its Edge browser is built on top of Google’s Blink engine.

There are only three major browser engines left — Apple’s WebKit, Google’s Blink and Gecko from Mozilla. Apple’s WebKit mainly runs on Apple devices, making Gecko the only cross-platform challenger to Blink.

Remedies in the U.S. v Google search case

There are only three major browser engines left — Apple’s WebKit, Google’s Blink and Gecko from Mozilla. Apple’s WebKit mainly runs on Apple devices, making Gecko the only cross-platform challenger to Blink.

Remedies in the U.S. v Google search case

So how do browser engines tie into the search litigation? A key concern centers on proposed contractual remedies put forward by the DOJ that could harm the ability of independent browsers to fund their operations. Such remedies risk inadvertently harming browser and browser engine competition without meaningfully advancing search engine competition.

Firefox and other independent browsers represent a small proportion of U.S. search queries, but they play an outsized role in providing consumers with meaningful choices and protecting user privacy. These browsers are not just alternatives — they are critical champions of consumer interests and technological innovation.

Rather than a world where market share is moved from one trillion dollar tech company to another, we would like to see actions which will truly improve competition — and not sacrifice people’s privacy to achieve it. True change requires addressing the barriers to competition and facilitating a marketplace that promotes competition, innovation and consumer choice — in search engines, browsers, browser engines and beyond.

We urge the court to consider remedies that achieve its goals without harming independent browsers, browser engines and ultimately without harming the web.